1964年的一个湛蓝天空下,东京奥运会开幕了。奥运会被视为日本在二战后经济腾飞的象征,自此之后,日本成为美国之后的全球第二大经济体。2021年7月23日,2020东京奥运会因疫情足足推迟了一年之久,看台上不允许有其他观众。而在场外,不时就能听到民众呼吁“停止奥运”的呐喊声。

1964年东京夏季奥运会开幕式上飘向体育场上空的气球。

The 1964 Games Proclaimed a New Japan. There’s Less to Cheer This Time.

Under crisp blue skies in October 1964, Emperor Hirohito of Japan stood before a reborn nation to declare the opening of the Tokyo Olympic Games. A voice that the Japanese public had first heard announcing the country’s surrender in World War II now echoed across a packed stadium alive with anticipation.

在1964年10月的一个湛蓝天空下,日本的裕仁天皇站在一个重生的国家面前宣布,东京奥运会开幕了。日本民众第一次听到他的声音是宣布日本在第二次世界大战中投降,这个声音如今回荡在座无虚席、充满期待的体育场里。

On Friday, Tokyo will inaugurate another Summer Olympics, after a year’s delay because of the coronavirus pandemic. Hirohito’s grandson, Emperor Naruhito, will be in the stands for the opening ceremony, but it will be barred to spectators as an anxious nation grapples with yet another wave of infections.

东京又一届夏季奥运会的开幕式将在本周五举行,这届奥运会因新冠病毒大流行推迟了一年。裕仁天皇的孙子德仁天皇将出现在开幕式的看台上,但看台上不允许有其他观众,因为这个焦虑的国家正在努力应对又一波新冠病毒感染。

For both Japan and the Olympic movement, the delayed 2020 Games may represent less a moment of hope for the future than the distinct possibility of decline. And to the generation of Japanese who look back fondly on the 1964 Games, the prospect of a diminished, largely unwelcome Olympics is a grave disappointment.

对于日本和奥林匹克运动来说,推迟举行的2020年奥运会很难展现充满希望的未来,更多的是在预示着下滑和衰退。对深情回顾1964年奥运会的那代日本人来说,这届远不如前、在很大程度上不受欢迎的奥运会的前景令人深感失望。

从一个摩天大楼的观景层看到的东京新国家体育场。

“Everyone in Japan was burning with excitement about the Games,” said Kazuo Inoue, 69, who vividly recalls being glued to the new color television in his family’s home in Tokyo in 1964. “That is missing, so that is a little sad.”

“那时候每个日本人都对奥运会兴奋不已,”现年69岁的井上和夫(Kazuo Inoue,音)说,他清楚地记得,1964年在东京家中,他被新买的彩色电视机里播放的赛事深深吸引。“这次缺少那种兴奋,所以有点难过。”

Yet the ennui is not just a matter of pandemic chaos and the numerous scandals in the prelude to the Games. The nation today, and what the Olympics represent for it, are vastly different from what they were 57 years ago.

不过,这种厌倦不只是新冠病毒大流行的混乱和奥运会前的无数丑闻造成的问题。今天的日本、以及奥运会让其展示的东西,已经与57年前有了很大的不同。

The 1964 Olympics showed the world that Japan had recovered from the devastation of the war and rebuilt itself as a modern, peaceful democracy after an era of military aggression. Highways and the bullet train were rushed to completion. With incomes rising, many Japanese families like Mr. Inoue’s bought televisions to watch the Games, the first to be broadcast live by satellite around the globe.

1964年的奥运会让日本向全世界展示,这个国家已从战争的破坏中恢复过来,经历了军国主义时代,日本已经重建为一个现代的、和平的民主国家。日本迅速地完成了高速公路和高速列车的建设。随着老百姓收入的增加,许多像井上这样的日本家庭为观看奥运会购买了电视机,那是奥运会赛事首次通过卫星在全球进行现场直播。

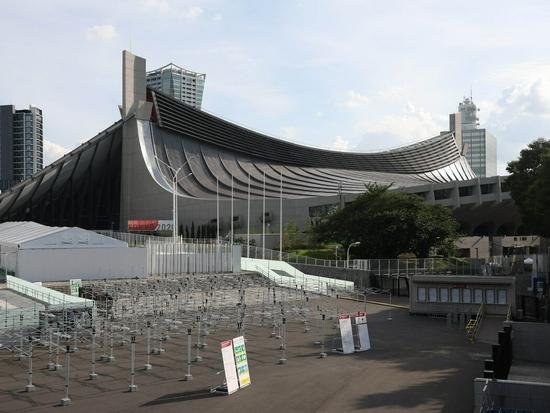

大约在1964年9月从空中拍下的日本东京国立代代木竞技场像片。

2021年7月15日的国立代代木竞技场。

This time around, Japan is a mature, affluent nation. But its economy has been stagnant for much of the past three decades, leaving growing numbers of people behind. One in seven children live in poverty, and many workers are in contract or part-time jobs that lack stability and pay few benefits.

举办这次奥运会时,日本已是一个成熟、富裕的国家。但日本经济在过去30年的大部分时间里一直停滞不前,越来越多的人被甩在了后面。每七名儿童中就有一名生活贫困,许多工人从事缺乏稳定性、没有多少福利的合同工或兼职工作。

It is a much older nation now, too. When Hirohito opened the Summer Games, just 6 percent of the population was 65 or older. Today, the figure is more than 28 percent, and the fertility rate is almost half that of 1964. The population has been shrinking since 2008.

日本现在也是一个更加老龄化的国家。裕仁天皇宣布夏季奥运会开幕时,年龄在65岁以上的人只占全国人口的6%。这个比例如今已超过了28%,而生育率几乎降到了1964年的一半。日本的人口自2008年以来一直在减少。

The 1964 Tokyo Olympics are often regarded as the point when Japan pivoted into prosperity. Within four years, Japan became the world’s second-largest economy, behind the United States, its for mer occupier. (It has since fallen to third, behind China.) As many Japanese entered the middle class, they bought not just televisions, but other modern appliances like washing machines, refrigerators and vacuum cleaners.

1964年东京奥运会常常被认为是日本走向繁荣的转折点。在奥运会之后的四年时间里,日本成为了世界第二大经济体,仅次于它以前的占领者美国。(日本经济后来降到全球第三,排在中国之后。)随着许多日本人进入中产阶级,他们不仅购买了电视机,还购买了洗衣机、冰箱和吸尘器等其他现代家用电器。

Japan is again approaching a turning point, one whose outcome depends on how the government, corporations and civil society respond to a shrinking and aging population.

日本正再次面临一个转折点,其结果将取决于政府、企业和公民社会如何应对人口萎缩和老龄化的问题。

Back in 1964, there was “a sense of Japan in motion and a sense of a country with a future,” said Hiromu Nagahara, an associate professor of history at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Now, it’s “a country that has lost confidence and a country whose political elites feel very intensely that loss of confidence.”

1964年的时候有一种“日本在运转、是一个有未来的国家”的感觉,美国麻省理工学院(Massachusetts Institute of Technology)历史系副教授永原宣(Hiromu Nagahara)说。现在,日本是一个“迷失了信心的国家,是一个国内政治精英强烈感受到这种迷失的国家”。

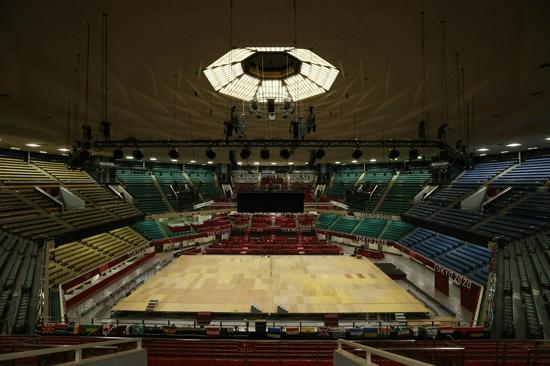

位于东京千代田区的日本武道馆内貌。

When Tokyo bid for the 2020 Games, the prime minister at the time, Shinzo Abe, framed it as a symbol of triumph over a devastating earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disaster in 2011. That message has been overtaken by a new narrative: that the Games represent a global effort to overcome the pandemic.

东京申办2020年奥运会时,时任首相的安倍晋三(Shinzo Abe)将其表述为日本战胜了2011年的毁灭性地震、海啸和核灾难的象征。那这个信息已被一种新说法所取代:奥运会代表着全球战胜新冠病毒大流行的努力。

The Japanese people, who mostly oppose holding the Games, aren’t buying either message. The nuclear cleanup is far from complete, and the Games are being held amid a state of emergency as coronavirus cases have reached a six-month high in Tokyo. Those increases have been compounded by daily announcements of positive cases in the Olympic Village, reminding everyone of the enduring power of the virus.

大多数日本人反对举办奥运会,他们对这两种信息都不买账。核电站的清理工作远未完成,由于东京的新冠病毒确诊病例已达到六个月来的最高水平,奥运会是在紧急状态下举行的。奥运村每天都有病毒检测阳性被公布,确诊病例数进一步增多,也使人们想起新冠病毒的持久威力。

And with spectators barred from all but a few events, there is little upside for hotels, restaurants, retailers and other businesses.

除少数几项赛事外,其他所有赛事都禁止现场观众进入,这让酒店、餐馆、零售商和其他生意都得不到什么好处。

“I feel sorry for the tourism business or hotels,” said Ikuzo Tamura, 84, who sold commemorative cloth wraps in the Olympic Stadium in 1964. “They don’t have the same opportunity as we did. I don’t think someone should be blamed, but in this situation, people have no choice but to endure.”

“我为旅游业和酒店感到遗憾,”现年84岁的田村郁三(Ikuzo Tamura,音)说,1964年时,他曾在奥林匹克体育场卖过纪念布包。“他们没有我们那时的机会。虽然我认为不应该责备某个人,但在这种情况下,人们别无选择,只能忍受。”

At this point, Japan’s best hope may be to showcase its crisis management skills by pulling off the events without any large-scale outbreaks.

到了这个时候,日本最大的希望也许是展示本国的危机管理能力,在不发生任何大规模疫情暴发的情况下把赛事办成。

位于东京千代田区的日本武道馆外观。

Historians point out that the 1964 Games did not go as well as gauzy-eyed citizens might recall. Two top officials resigned amid public criticism of Japan’s decision to send a team to the 1962 Asian Games, whose host country, Indonesia, excluded athletes from Israel and Taiwan, said Yuji Ishizaka, a sports sociologist at Nara Women’s University. And up to a year before the 1964 Olympics, only about half of the public supported hosting the Games.

历史学家指出,1964年的奥运会并不像把记忆美化的市民们心目中那样顺利。奈良女子大学(Nara Women’s University)的体育社会学专家石坂友司(Yuji Ishizaka)说,有两名高级官员在公众批评日本派队参加1962年亚运会后辞职,那届亚运会的主办国印度尼西亚将以色列和台湾的运动员排除在外。而且,在1964年奥运会开幕前的一年里,只有大约一半的公众支持举办奥运会。

Still, the hope of any Olympics is that, once the Games start, the athletic competition comes to the fore. What people remember best from 1964 is the victory of the Japanese women’s volleyball team, a group of factory workers who snatched the gold medal from the Russians; or the men’s gymnastics team, which won a group gold medal, becoming heroes.

不过,举办任何一届奥运会的希望都是,一旦赛事开始,注意力就会转移到体育竞赛上去。1964年奥运会给人们留下最深刻记忆的是日本女子排球队夺得冠军,这个由工厂工人组成的球队从俄罗斯人手中夺得了金牌;还有日本男子体操队,他们赢得了团体冠军,成了英雄。

This year, even without live audiences, the drama will still be present and televised. But it will be tempered.

今年,即使没有现场观众,仍有激动人心的赛事和直播。但不会那么热火。

“For athletes, for me, having spectators gives you so much power,” said Shuji Tsurumi, 83, a gymnast on the 1964 team who also won three individual silver medals.

“对运动员来说,对我来说,现场观众能给人带来非常大的力量,”现年83岁的鹤见修治(Shuji Tsurumi)说。他是参加了1964年奥运会的体操队员,赢得了三枚个人银牌。

“You have to feel the athlete’s breath on your skin, the air in the stadium, the tension of the others around you waiting for a successful landing,” he added. “Without that, it’s not the same.”

“你需要在皮肤上感觉到运动员的呼吸,感觉到体育馆里的气氛,以及周围等着看你成功落地的人的紧张情绪,”他补充说。“没有这些,就不一样了。”

Yoshiko Kanda, a member of the victorious volleyball team in 1964, said that the crowd’s cheers were “the biggest reminder of why I was competing.”

在1964年奥运会上夺得女子排球金牌的日本队队员神田好子(Yoshiko Kanda,音)说,观众的喝彩声“是对我为什么参加比赛的最大提醒”。

“Without this feeling in the air, I bet many athletes are struggling,” said Ms. Kanda, 79, who competed under her unmarried name, Matsumura. “In 1964, the environment, the air, the feeling in society was burning with excitement,” she added. “Compared to the ’64 Olympics, it will be so lonely.”

“没有这种气氛的话,我敢打赌很多运动员都会很吃力,”现年79岁的神田好子说,她参赛时用的是婚前姓氏松村(Matsumura)。“1964年的环境、气氛以及社会上的感觉充满了强烈的兴奋,”她还说。“与1964年的奥运会相比,这次的感觉太孤独了。”